In front of the camera

Roma photographs from the 19th and early 20th centuries

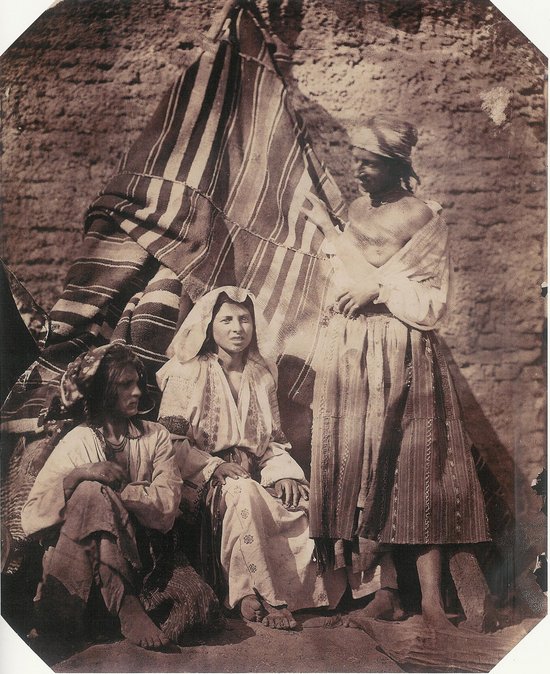

Ludwig Angerer: “Gypsies,” the photo was taken in 1855/56 in Wallachia, near Bucharest, salted paper print, Picture Archive of the Austrian National Library, Vienna.

Carol Szathmári: “Gypsy Woman,” circa 1863, Carte-de-visite.

"Wandering Gypsies", colored photo postcard, Transylvania, after 1900, K. Klein Collection.

From the mid-19th century onwards, photography played a central role in the visual representation of the minority. The photographic positions of photographers, their perspectives, interests, and photographic results varied greatly over the years.

In his 1845 novella Carmen, French writer Prosper Mérimée (1803–1870) claimed that “gypsies” were easier to recognize by their appearance than to describe.[1] With this thesis, which he puts into the mouth of his narrative character, he assigns a prominent role to visuality, the sense of sight, in the classification and racist inclusion and exclusion of the minority. The frame narrative of Carmen is set in 1830, shortly before the first public presentation of photography. In 1845, when the text was written, the author had certainly already heard about the triumph of the new medium and may even have seen the first images. It is therefore perhaps no coincidence that a new discourse on the visual representation of minorities emerged during these years. In the coming decades, photography would be at the center of these discursive efforts to circumscribe and capture the supposed “essence” or core of the difference from mainstream society by visual means.

Even though practically all photographers who photographed Roma and Sinti between the first photographic recordings of the minority in the 1850s and the middle of the 20th century were committed to an – often voyeuristic – view from the outside and usually also from above (i.e., firmly embedded in the hierarchies of seeing), their photographic positions, their respective perspectives, interests, and photographic output did not remaine the same over the many decades. Not only did their cameras, equipment, the occasions for the photographs, and the locations of the shots change, but so did the use of the images. Their handling, further processing in the media, and reception were subject to major changes and economic cycles from the mid-19th century onwards. In the following, some of these media-historical shifts in the photographic view of Roma and Sinti from the beginnings of photography to the middle of the 20th century will be traced using selected photographers as examples. The focus of interest is on the photographers' view and the role of images in the field of society.

When Ludwig Angerer (1827–1879), a military pharmacist and photographer from the Vienna area, came to Romania in the summer of 1854 as a member of the Austro-Hungarian military and stayed for two years, he took the world's first photographs of Roma and Sinti.[2] Like many pioneers of early photography, he was self-taught and interested in science, so he was familiar with the physical and chemical processes involved in photography. Angerer was equipped with a large-format, heavy plate camera including a tripod, which he had brought with him from Vienna, as well as glass plates in the very large format of 34 x 24 cm.

Unlike many of his other portraits, Angerer always photographed members of the Roma community outdoors. In addition, he almost always depicted the “gypsies” in groups. All of his Roma photos are clearly staged. Some of the scenes are arranged in a pyramid shape. A child crouches on the ground, directly on the bare earth, while another naked child sits in the middle. They are framed by two women (one of whom is smoking a pipe), behind whom we see a man with his head bowed. This pyramid-like staging also appears in other pictures, this time featuring only women, two of whom are sitting and one standing. Behind them is a striped cloth. It is a tent that has been set up in front of a wall for the photo shoot. What is also striking here are the exposed bodies; all of the subjects are barefoot, and one of the women is wearing a wide-open dress that exposes her breast.

Contrary to what one might assume, the first photographic portraits of “gypsies” did not lead to a shift toward sober documentation. On the contrary, the figure of the “gypsy” entered the stage of photography as a type staged in front of the camera—and as a group. In the 1850s, the process of taking pictures was still laborious: the huge apparatus could not be set up without causing a stir, the negative plates had to be made light-sensitive by hand using chemicals, and the exposure time was still quite long, so the models had to stand still for a long time. In early photographic representation, Angerer and many other photographers after him visibly borrowed from other graphic arts, such as painting and graphic design, which had long provided typological “gypsy” images. What's more, photographers worked to suit the tastes of the general public. They produced mainstream images and mainly catered to current fashions and conventions of perception.

Carol Popp de Szathmári (1812–1887), who came from Transylvania and was trained as a painter, also took photographs in Romania during the Crimean War. He exhibited his pictures in the major cities of Europe or sold them as templates for engravings to international newspapers.[3] In addition to war photographs, he also produced typological scenes of the native Romanian population, including pictures of Roma people. Unlike Angerer, Szathmári began producing his typological portraits in the studio. He was not interested in sober documentary depictions; on the contrary, the scenes and “types” were staged in great detail, as in Angerer's work, with many accessories, items of clothing, backgrounds, and visual elements corresponding to the imagination. These type portraits enjoyed great popularity among the bourgeois public from the 1860s onwards.

Not only in Romania, but also in numerous other European countries, “gypsy” portraits taken in studios began to appear in the 1860s. During these years, these scenes could be incorporated into the broad spectrum of equally popular photo series of traditional costumes and “folk types.” Cartes-de-visite photographs (measuring approximately 6 x 9 cm) and cabinet cards (approximately 10 x 15 cm) were particularly popular during this period. Due to their small format of Cartes-de-visite, which made retouching unnecessary, and mass production, the price of these pictures could be significantly reduced. This was accompanied by an enormous increase in the distribution of these small pictures. Until around 1900, photographic images of Roma and Sinti were mainly distributed in these two formats. In addition, from the 1860s onwards, stereo photographs also became popular and were produced in large numbers. The majority of photographs of Roma and Sinti distributed in the 19th century were therefore highly synthetic images in terms of their production and staging, with their scenes designed as artificial products in the studio.

The process of Cartes-de-visite photography coincided with the self-confident staging of the young bourgeoisie. Mass-produced photography served mainly to reproduce bourgeois portraits. At the same time, however, these small portrait photographs also drew and reinforced the social, ethnic, and geographical boundaries of these self-confident social groups. This was achieved by integrating typologies that deviated from the norm, that were “foreign” and exotic, into the visual spectrum of what was considered worthy of being photographed as a kind of negative schema. The early mass products of bourgeois photographic culture therefore very clearly illustrate both intertwined strategies: that of social, ethnic, and national demarcation, but also that of exclusion and demarcation.

The staging of the photographically illustrated picture postcards, which circulated in enormous numbers since the turn of the 20th century, are in some respects similar to the production conditions of the visiting card pictures described above. On the stage of picture postcards, too, Roma and Sinti appear almost exclusively as “types.”[4] But there are also differences. Unlike the Cartes-de-visite pictures, the models were usually photographed outdoors and no longer in the studio. The picture postcards embed the “gypsies” in a supposedly typical rural landscape, give them attributes of being on the move (usually tents or simple, open huts) and very often bathe the scene in colorful hues. However, we also repeatedly encounter “gypsies” as individual types, as representatives of their “typical” professions: tinker, spoon maker, bear leader, etc.

The photographic templates for the picture postcards were mostly produced by local photographers. Here and there, the commissions also came directly from large postcard producers. In the printed version of the images, the photographer usually took a back seat to the name of the postcard manufacturer; only in a few cases is he explicitly named. The dealers were both local companies and internationally active wholesalers. The reproduction and printing techniques varied, ranging from cheaper autotypes (screen printing), which were printed in black and white or colored, to more expensive, mostly colored phototypes. Since the motifs were often kept in stock for years, sometimes even decades, individual photo templates appear in numerous variations and with different labels.

At the turn of the 20th century and in the first third of the 20th century, a new type of photographer emerged who was interested in the photographic representation of Roma and Sinti. During these years, a number of ethnological researchers set out to explore the supposedly static and archaic (counter)world of the “gypsies.” In order to uncover this world, ethnologists and linguists believed it was necessary to approach their “objects of study” using scientific methods. The German folklorist and photographer Martin Block (1891–1972) went so far as to immerse himself incognito in this counterworld during his ethnological field studies, which he conducted during the First World War under the protection of the German occupation forces in Romania. He learned the languages of the “Gypsies,” dressed like them, and pretended to be a “Gypsy.”[5]

“Truth and objectivity,” writes Block, “are particularly beneficial to Gypsy research. The study of Gypsies must be geared toward a critique that scrutinizes the material that has been handed down and, by means of newly collected material, checks its authenticity.” He went on to say: “So let us put all theories aside and strip away all facts shrouded in such hasty interpretations.”[6] Ethnologically oriented scientists, many of whom also took photographs, used their cameras to capture activities, work processes, and often everyday scenes. They not only documented groups, but also began to capture individual persons in their images. And they introduced another change: the subsequent coloring of images, which was widespread in both visiting card photography and postcards, now disappeared: the ethnological photographic gaze favored “black and white,” which was considered more scientific. Even though these ethnological “Gypsy” photographs pretend to offer an unadulterated, sober, and scientific view of “real Gypsy life,” they nevertheless reproduce numerous clichés and typological and racist attributions that were widespread in science.

Ethnological photo expeditions were particularly numerous in the context of the First World War. Ethnologists often worked in the conquered territories of Eastern and Southeastern Europe. The signs and effects of racist and colonialist conquests also found their way into the visual world of the ethnologists who accompanied these expeditions or conducted research in their shadow. Only some of their photographic spoils were published. Many of the images were often stored in archives for decades without the racist project of their science being subjected to fundamental criticism and reappraisal.[7]

A.H.

[1] The work and its countless adaptations and reworkings (e.g., in music history) had a major influence on images of the Roma. Its long-lasting media echo has contributed greatly to the proliferation and perpetuation of Roma clichés and projections.

[2] On Ludwig Angerer's Roma photographs, see Anton Holzer: In the Shadow of the Crimean War. Ludwig Angerer's photographic expedition to Bucharest (1854 to 1856) in: Peter Pakesch, Verena Formanek (eds.): Seeing Carmen. Goya. Courbet. Manet. Nadar. Picasso, Cologne: Walther König, 2005, pp. 284–337. (The text first appeared in German in the journal Fotogeschichte. Beiträge zur Geschichte und Ästhetik der Fotografie, No. 93, 2004, pp. 23–50). In the shadow of the Crimean War (1854–1856), Austria-Hungary had exploited the power vacuum in the Balkans and occupied the two principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia in 1854.

[3] On Szathmári, see Adrian-Silvan Ionescu: Fotografie und Folklore. Zur Ethnofotografie im Rumänen des 19. Jahrhunderts, in: Fotogeschichte. Beiträge zur Geschichte und Ästhetik der Fotografie, No. 103, 2007, pp. 47–60.

[4] For more details, see: Peter Bell: „Balkan-Typen“. Bildpostkarten als inszenierte Momentaufnahmen des frühen 20. Jahrhunderts, in: Frank Reuter, Daniela Gress, Radmila Mladenova (eds.): Visuelle Dimensionen des Antiziganismus, Heidelberg 2021, pp. 203–236.

[5] Martin Block: Die materielle Kultur der rumänischen Zigeuner. Versuch einer monographischen Darstellung [1923]. Edited and published with a biography of the scholar by Joachim S. Hohmann, Frankfurt am Main 1991.

[6] Ibid., p. 17.

[7] It was not until the mid-1990s that critical reception and reappraisal began. See, for example, Katrin Reemtsma: „Zigeuner“ in der ethnographischen Literatur. Die „Zigeuner“ der Ethnographen, Frankfurt am Main 1996.