Barthes' violinist

A photo from the “camera lucida” - reconsidered

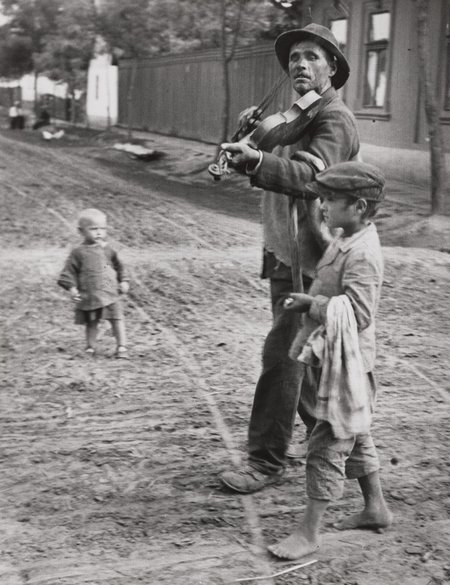

André Kertész: Wandering violinist, Abony, Hungary, 1921

A famous photo by André Kertész from 1921, analyzed by Roland Barthes in “camera lucida” (1980), shows how much the photographic figure of the “gypsy” functions as a wishful idea and projection.

The book by Polish author Andrzej Stasiuk, On the Way to Babadag (2004), features a photo by Hungarian photographer André Kertesz. The image is titled “The Wandering Violinist.” Stasiuk reports that this photo moved him deeply when he first saw it. What's more, it accompanied him on all his travels in the Balkans. “It is not impossible,” he writes, “that everything I have written so far began with this photograph.”[1] The picture was taken on June 19, 1921, in a small town called Abony, not far from the city of Szolnok in the Hungarian lowlands. When he photographed this scene, Kertesz was 27 years old and still completely unknown as a photographer. Four years later, he left Hungary and went to Paris, and later to New York. He became famous, and the photo he had taken in 1921 also became famous. Today, the photograph from Abony is one of his most famous works.

Andrzej Stasiuk has examined the photo very closely. Let's follow his description: “A blind violinist crosses the street and plays. He is accompanied by a barefoot boy of about ten years old wearing a peaked cap. The musician wears worn-out shoes. His left foot steps straight onto the narrow track left by a cart with iron wheels. The road has no solid surface. It is dry. The boy's feet are not dirty, the track of the narrow wheels is flat and barely visible. It curves gently to the left and disappears into the slightly less sharp background of the picture. A wooden fence runs along the road, and part of a house can be seen: the sky is reflected in the windows. A little further on is a white chapel. Behind the fence are trees. The musician has turned his eyes inward. He walks and plays for himself and the invisible space that surrounds him. Apart from the two of them, there is only a small child on the road. It faces them but looks into the distance. The day is cloudy; neither objects nor figures cast shadows. The violinist has a cane hanging from his left arm and his companion is carrying something that looks like a small blanket. They are only a few steps away from the edge of the picture. Soon they will disappear, the music will fall silent. Only the little boy, the street, and the car tracks remain in the photograph.“[2] So much for Stasiuk's description. ”For four years,” he continues, “this image has been haunting me. Wherever I go, I am always on the lookout for its three-dimensional, colored versions, and I often think I have found them. (...) The space in this photo hypnotizes me, and all my travels serve only the purpose of eventually finding the hidden entrance to its interior.”[3]

Stasiuk is not the first author to be struck by the “magic” of this image and to fall under its spell. Twenty-five years earlier, Roland Barthes approached the same photo with a similar fascination in his book Camera Lucida. He also reproduces the photo, and he too, he writes, finds that this image triggers a series of associations. In Barthes's book, the photograph is titled “The Ballad of the Violinist Abony.” Strangely enough, the place name Abony has now (at least in the German-language edition) become a person's name (a translation error?). Another shift is also noticeable: in Barthes's book, the violinist is a gypsy. “There is,” he writes about the picture, “a photograph by Kertesz (1921) depicting a gypsy violinist, blind, led by a boy (...).”[4] And further: “The nature of this dirt road gives me the certainty of being in Central Europe; I recognize the referent (...), I recognize with every fiber of my being the small villages I passed through long ago on my travels in Hungary and Romania.”[5]

Is the violinist really a “gypsy”? We don't know. In any case, there is no indication of this in André Kertesz's own work, and the current copyright holder, the French Ministry of Culture, also refers to the picture as “wandering violinist" and not “gypsy violinist”, as Barthes does. Nevertheless, the connection between the “wandering violinist” and the alleged “gypsy” has persisted for years. We encounter this photo again and again in catalogs and exhibitions under this expanded caption, which actually marks an expanded context of association. André Kertesz's photo is an example of the typologized and, precisely for this reason, highly ambivalent image of the “gypsy.” This image is strangely indeterminate, deriving its meaning from a few visual ingredients. Here it is the violin, the violinist's clothing, the ground, etc. Barthes is aware of how much he is subject to a culturally preformed classification when he assigns the violinist to the East: “(...) the road made of stamped earth; the nature of this dirt road gives me the certainty of being in Central Europe.”[6] With similar “certainty,” Barthes turns the violinist into a “gypsy.” Here, too, even if he does not explicitly name it, he follows a chain of associations, voicing what others before him had already formulated: the wandering violinist is a “gypsy.” The example shows that the image of the “gypsy” is also created in the mind. They do not arise out of nowhere, they are not simple prejudices, but rather embody a long tradition of role models.

(…)

Once again: Abony

Andrzej Stasiuk was so captivated by the blind gaze of the wandering violinist from Abony that he decided to visit the place where the photo was taken. One day in winter, he got in his car and drove off in the direction of Abony. “I found nothing there,” he reports. “I filled up at the exit to Budapest, then drove around the small town in four minutes. A woman was hanging up laundry, and that was it—the houses were over.” The place, the scene, the image that had haunted him again and again remained empty. It was only from a picture book about André Kertesz, which the author later bought, that he learned that the little boy at the violinist's side was the photographer's son. And in this picture book, he also found a quote from Kertesz himself, who later recalled the photograph: "I took the photo on a Sunday. The music woke me up. The blind violinist played so beautifully that I can still hear him today.“[7]

English excerpt from:

Anton Holzer: Faszination und Abscheu. Die fotografische Erfindung der „Zigeuner“ in: Fotogeschichte. Beiträge zur Geschichte und Ästhetik der Fotografie, No. 110, 2008, pp. 45-56.

[1] Andrzej Stasiuk: Unterwegs nach Babadag (On the Way to Babadag), Frankfurt am Main 2005, p. 197. The original Polish edition was published in 2004.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., p. 197 f.

[4] Roland Barthes: Die helle Kammer (Camera Lucida). Bemerkung zur Photographie, Frankfurt am Main 1985 (french first edition: 1980), p. 55.

[5] Ibid., p. 58.

[6] Ibid., p. 55.

[7] Andrzej Stasiuk, Unterwegs nach Babadag, Frankfurt 2005, p. 226.