A different gaze?

Photos that subvert the prevailing visual regime

Sándor Ùjházy: Roma couple in wedding attire, photographed in 1911 in Karcag, Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County, Hungary.

Members of the Association of Roma Musicians on the steps of the National Museum in Budapest, photographed in the 1930s by an unnamed photographer from the Hungarian Film Office.

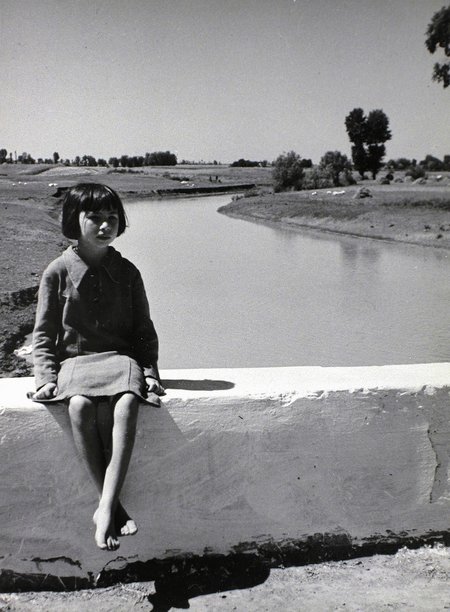

Kata Kálmán: “Roma girl on stone bridge,” photo taken in 1937 in Jászjakóhalma, Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County, Hungary.

Until the mid-20th century, there were very few photographs that challenged the established visual regime regarding Roma and Sinti. Three of these images, which suggest alternative visual solutions, are presented here as examples.

Until the mid-20th century, not only was the visual regime between non-Roma photographers and Roma subjects virtually unbroken, but the forms of staging also generally perpetuated traditional prejudices and clichés. Photographs from these years that challenge these hierarchies of seeing are rather rare. But every now and then there are images that, if not dissolving the dominant axes of vision and pictorial formulas, at least relativize them to some extent. The three photographers whose images are presented below, together with those portrayed, have adopted highly diverse pictorial strategies.

The first photo was taken in 1911 in a rural area in Hungary.[1] It is one of the few photographs in which members of the Roma community are shown differently than in the familiar “nomadic” subjects. We see a wedding couple. The young woman is dressed entirely in white. The man stands next to her in a suit, his top hat placed on a chair beside him. Both are looking at the camera. The photo, taken by Sándor Ùjházy, was taken outdoors. We quickly notice how fragile the superficial veneer of bourgeois ritual is: the poor trousers, the simple shoes, the rough hands protruding from the white shirt sleeves. We immediately see that the two people portrayed belong to the lower class. But would we think that the two people are Roma?

The bride and groom apparently ordered the wedding photo from a local photographer. It is clear that the photographic wedding ritual, which began in bourgeois circles in the mid-19th century, is quite foreign to the two protagonists. They do not pose confidently in front of the camera, but stand rather awkwardly in front of the photographer. While at the beginning of the 20th century the vast majority of wedding photos were taken in studios, our two protagonists have posed outdoors. They may have commissioned a traveling photographer, who was cheaper.

A second example: The photograph was taken in Budapest in the 1930s.[2] We see a group of well-dressed men. All of them are wearing suits, ties or bow ties, and white shirts. Some of them are wearing hats. The men have positioned themselves on the steps of the National Museum, presumably under the careful direction of the photographer, so that all their heads are clearly visible. According to the caption, the men are members of the Association of Hungarian Romani Musicians. They had been organized as a union in Hungary for many years to represent their interests. Within the social stratification of Hungarian Roma groups, Roma musicians, especially the most famous among them, occupied the highest positions. Unlike their rural counterparts, they were often perceived by mainstream society as urban protagonists of a quasi-national musical genre.

We do not know who took this group photo. But one thing is clear: the photographer carried out the commissioned work in a completely different way than those photographers who, in their hunt for folkloric “gypsy” scenes, captured the supposedly “typical” attributes. The clients wanted a proud bourgeois group photo. And that's what they got.

One last photo: a young girl sits on a brick bridge railing.[3] She is dangling her feet. Her gaze is not directed at the camera. Behind the girl, a wide river landscape can be seen. The photo was taken in 1937 in a small town in Hungary. The photographer's name is Kata Kálmán. She called the photograph “Gypsy Girl on the Stone Bridge.” In the picture itself, Kálmán rejects any folkloric shortcuts. The girl is not presented (as was previously customary) as part of a predefined group, “the Gypsies.” Nor is she classified by her clothing, posture, surroundings, or other identifying attributes. On the contrary, there is no indication in the image that she belongs to a collective.

Kata Kálmán was a member of the left-wing opposition movement during the interwar period and began taking photographs in 1931 (at the age of 22). In 1934, she began (together with Iván Boldizsár) a social documentary photo and research project on the impoverished rural population in the villages of the Hungarian lowlands. In 1937, this resulted in the volume “Tiborc,” a book of photos and interviews that made her famous. During the interwar period, Kálmán also planned a photo book entitled “Gypsies.” It would have been the first modern photo book on this subject. However, due to the war, it was never realized.

Kálmán continued her photographic research in the 1950s. In 1955, she published a phototypesetting volume on “Tiborc,” in which she revisited the subjects of the first volume and documented the changes. She did not return to the subject of the Roma after 1945. It would hardly have been possible to make a before-and-after comparison. For, as we know, in the case of the Roma, there was no longer an “after.”

A.H.

[1] Photo from: Gerhard Baumgartner, Tayfun Belgin (Hg.): Roma & Sinti. „Zigeuner-Darstellungen“ der Moderne, catalog accompanying the exhibition at the Kunsthalle Krems, Krems 2007, p. 29.

[2] Ibid., pp. 114/115.

[3] Ibid., p. 87.