Hierarchies of Seeing

Roma and Sinti in Photography

Comparison of two different portraits: on the right, the face of a ‘middle-class’ woman, taken in close-up; on the left, a ‘gypsy mother’ with child, taken outdoors. From: ‘Fotosport,’ amateur photography section of the Czech magazine Pestrý Týden, 21 April 1934, p. 14.

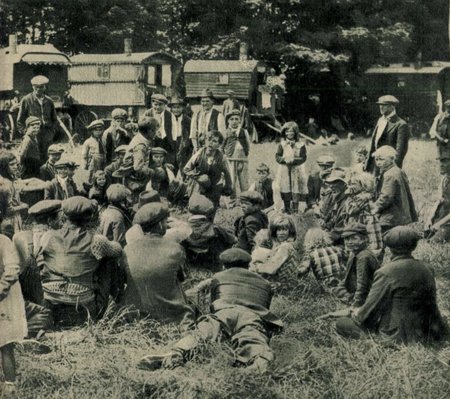

Photo report on Roma attending the horse races in Epson, Great Britain, Tolnai Világlapja, 16 June 1937, p. 9.

The history of photographic representations of Romani and Sinti people is marked by extreme social inequality between those who stood in front of the camera and those who operated it.

The representation and public perception of Roma and Sinti people is characterized by clichés, projections, and attributions to a far greater extent than the perception of other European minorities.[1] Photographs of Romani and Sinti people have been made since the mid-19th century. But it was only after 1900, and especially in the interwar period, that these photos reached a mass audience through reproduction in illustrated newspapers and magazines. The photographs published in the press have left their mark on collective perception to this day. Contemporary visual representations of Romani and Sinti people still draw on image patterns and conventions of representation that were published in the early mass media, illustrated newspapers, but also picture postcards. The history of photographic representations of Romani and Sinti people is marked by extreme social inequality between those who stood in front of the camera and those who operated the equipment and edited the images for the media.

This imbalance becomes particularly clear when one considers that, until the mid-20th century, the vast majority of photographs of Romani and Sinti people in Europe were taken by photographers who did not belong to the group being portrayed. While the photographers are known in many (but not all) cases because their names were mentioned in the press, this is rarely true of those portrayed. In the vast majority of cases, Romani and Sinti people were portrayed anonymously, i.e. without their names being mentioned. It is also noteworthy that many of the images published in the media were taken outdoors in order to emphasise the non-sedentary, ‘nomadic’ culture.[2] Furthermore, the subjects are often depicted in groups rather than as individuals.[3]

All these forms of social and visual hierarchisation were also continued in the area of image processing and in the publication and reception process of the images. In the vast majority of cases, the people depicted in the photo reports and articles, the members of the Romani and Sinti communities, did not belong to the group of media professionals who prepared these images for print, reproduced them, commented on them and enriched or surrounded them with text. And in the case of (mainstream) newspaper reports, the large group of readers was not identical to the group of people portrayed.

Although the hierarchy of perspectives between the photographers and those portrayed appears immutable, and the social, political and media uses of photography largely excluded those portrayed from participating in the publication process, it would nevertheless be too simplistic to interpret the visual world of the Romani and Sinti exclusively from the perspective of passive victimhood and social and visual exclusion. In order to interpret the imagery of Romani and Sinti people not exclusively from the perspective of social and visual exclusion, it is necessary to critically question overly schematic and dichotomous comparisons between active photographers and passive subjects. A careful analysis of the surviving image collections also suggests other, more nuanced interpretations of the historical source material. It shows that there were repeated ‘cracks’ and disturbances in the underlying hierarchical photographic dispositif that occasionally called into question the pre-assigned roles between the photographer and the subjects. These disruptions did not lead to a reversal of the power relations in the photographic act. But they did open up small subversive spaces for the subjects depicted and gave them – albeit very limited – opportunities to influence the process of image-making. The subjects thus sometimes succeeded in evading the hegemonic gaze to a certain extent and/or even occasionally using the stage of photography for their own agenda.

A.H.

[1] Anton Holzer: Faszination und Abscheu. Die fotografische Erfindung der „Zigeuner“, in: Fotogeschichte. Beiträge zur Geschichte und Ästhetik der Fotografie, No. 110, 2008, pp. 45–56.

[2] The topos of ‘nomadic life’ was one of the most common projections in the press in the 1930s with regard to this minority. This contrasts with the fact that the vast majority of European Romani and Sinti people were settled during the interwar period.

[3] Numerous historical portrait photographs of members of the Romani and Sinti communities taken in photo studios have been preserved from the interwar period. However, such images were rarely published in the illustrated mainstream press of the 1920s and 1930s. They can be found, however, in minority magazines in some South-Eastern European countries during the interwar period.