Picture Stories

The role of photo reportage

Photo reportage on Spanish child dancers in Paris, Regards, 3 February 1938, pp. 12–13.

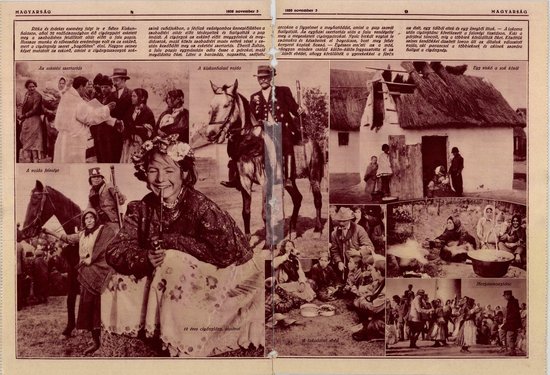

Photo reportage on Roma weddings in the Hungarian town of Kiskunhalas, 1935, A Magyarság képes melléklete, 3.11.1935, S. 8-9.

In the years around 1930, the photo reportage experienced a heyday in illustrated newspapers and magazines. Many picture-text stories dealt with the portrayal of Roma and Sinti.

The twentieth century has often been termed the century of images in a nod to the central role film and photography came to play as forms of mass media. Around 1930, novel designs for the visualization of news items were established, and with them new ways to connect images and text.[1] The significance of these innovations extended far beyond photo-reportage. News coverage, which had long been text-heavy in daily news publications, underwent a sudden and radical expansion: photography was no longer employed as an illustrative accompaniment to the text, but as a key narrative tool

The format of photo reportage played an important role in shaping images of Roma and Sinti in the interwar period. Many photo essays and picture reports on Romani and Sinti people from the interwar period, despite all their differences in structure and, in some cases, also in motifs, show parallels to visual explorations of non-European and colonial worlds.[2] As Ariella Azulay has pointed out, photography in the popular mass media functions, among other things, as a kind of playground and echo chamber for bourgeois desires and longings.[3] In a historical phase in which bourgeois self-image and self-confidence had become fragile, illustrated magazines repeatedly offered their reading and viewing “armchair travelers” photographic stories that took them on excursions into foreign, fascinating worlds, whose temptations and threats were presented in a dialogue between image and text.[4] It is precisely this overlap between bourgeois self-perception and projections of the foreign that is frequently found in the images and texts of the photo essays on Roma and Sinti examined in the project.

During the interwar period the media format of photo features and photo reportage flourished in many European countries, with mainstream newspapers and magazines reaching a mass audience.[5] The genre of reporting, which had developed in the late nineteenth century as a hybrid genre between journalistic reports and imagination,[6] was expanded and further refined by the media in the early twentieth century. During these years, the illustrated press became the most pervasive visual mass medium in the Western world, alongside film.[7] Changes also occurred in the photographers’ technical equipment. During World war I, the spread of new, light and fast cameras used by a rapidly growing number of amateur photographers increased at a remarkable tempo. Starting in the mid-1920s, these developments also became evident in press photography. Certain photographers began to rely on smaller, more mobile cameras, such as the Leica.

While in the early 1920s many illustrated weeklies and magazines initially published mainly individual photographs with commentary, from the mid-1920s much longer picture stories, often composed of complex elements and known as ‘photographic travel features’ and ‘photo features’, became popular in many magazines. The layouts of these image-text stories increasingly integrated graphics and typography, supplemented by text commentary, and anchored in different semantics according to the newspaper’s editorial slant and the perspective of the visual narrative.[8] Within the new format of photo reportage the number of photo series grew markedly, while that of individual photographs diminished. These photo series followed increasingly complex narrative structures, manifesting a close coupling of images and text. Photo-reportage also borrowed several narrative elements from film (e.g., close-ups, zooms, fade-ins and fade-outs, etc.).

Photo reports on Roma and Sinti are closely linked to the travel photo essays that became extremely popular in the 1920s, bringing insights into distant countries and ways of life that were described as “foreign” into middle-class living rooms. Photo Reports on Roma and Sinti also take readers on a journey to unknown worlds. Often, these places, described as exotic, the Roma and Sinti settlements portrayed in texts and images, are very close by, on the outskirts of European cities, but often they are far away, in rural areas on the European periphery and beyond. The narrative form of the report promises insights into a world that most readers do not usually travel to themselves, but which is made accessible to them in pictures and, even more so, in pictorial projections in printed form.

Modern photo reportage did not emerge in the 1920s as an isolated genre, but was embedded in cultural trends that had similar aesthetic and creative concerns. Reportage has been around in Anglo-Saxon New Journalism since the 1910s, and since the end of the First World War it has also become increasingly widespread in many European countries from Spain to Romania, for example in literature, journalistic reporting, film, and also the illustrated press. Its hallmark is often a sober, documentary, sometimes subjectively colored view that usually approaches only narrow sections of reality, but often seeks to recognize a larger whole in them.

While conventional photo reports combined photographs from a wide variety of sources into a pictorial story linked by text, the type of new photo reportage that became popular in many European countries around 1930 was characterized by the fact that the images often came from the same photographer, who documented an event from different perspectives. From the late 1920s onwards, photographers increasingly became authorial observers who left their personal mark on the pictorial story.

Photo essays on Roma and Sinti demonstrated a wide range of possible uses for photography. It was not uncommon for magazine and newspaper editors to use images that had been taken in very different contexts and often in several countries. They published photo stories in which the photos were only loosely related to the text, as well as reports that combined the authorial views of the author or photographer in text and images, and even fictional or semi-fictional reports in which the photographs accompanied the text in an associative manner. Sometimes the photographs were taken by the authors of the texts, but often the authorship of texts and images was separate and only brought together in the newspaper editorial offices.

The complex structure of the photo reportage format assigns very different narrative and rhetorical functions to the photos. In order to analyze them appropriately, the images must be viewed not only as individual objects (as singular photographs), but as interconnected, serially arranged images, each of which has very different intermedial narrative contexts. Sometimes their documentary use may predominate, in other cases the photos are used more metaphorically, associatively, or occasionally even as pictorial catalysts for fictional narratives.

A.H.

[1] On the development of the photo reportage media format, see Anton Holzer: Picture Stories. The Rise of the Photo Essay in Weimar Germany, in: International Journal for History, Culture and Modernity, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2018, pp. 1–39; see also Daniel H. Magilow: The Photography of Crisis: The Photo Essays of Weimar Germany, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012.

[2] On the interdependence between colonial projections and European self-images, see Anne Maxwell: Colonial Photography & Exhibitions. Representations of the ‘Native’ and the Making of European Identities, London, New York: Leicester University Press, 1999. See also Eleanor M. Hight, Gary D. Sampson (eds.): Colonialist Photography: Imag(in)ing Race and Place, London: Routledge, 2013.

[3] Ariella Azulay speaks of photography as a social “playground” that enables the bourgeoisie in particular to visually test collective self-concepts and boundaries. See: The Civil Contract of Photography, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

[4] Against a different social backdrop, (early) cinema played a similar role, offering temporary excesses from bourgeois and petty bourgeois life without fundamentally questioning its social coordinates.

[5] Mats Jönsson, Louise Wolthers, and Niclas Östlind, eds., Thresholds: Interwar Lens Media Cultures 1919–1939 (Cologne: Walther König, 2021).

[6] On the prehistory of reportage in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, and on the hybrid character of the medium, see Michael Homberg, Reporter-Streifzüge: Metropolitane Nachrichtenkultur und die Wahrnehmung der Welt 1870–1918 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017).

[7] See Tim Satterthwaite and Andrew Thacker, eds., Magazines and Modern Identities: Global Cultures of the Illustrated Press, 1880–1945(London: Bloomsbury, 2023).

[8] Cédric de Veigy, Michel Frizot, Vu: The Story of a Magazine, London: Thames & Hudson, 2009; Ulrich Hägele: Alexander Liberman, Marcel Ichac, Marc Réal: Die Illustrierte VU und ihre Fotomonteure 1930–1936, in: Fotogeschichte. Beiträge zur Geschichte und Ästhetik der Fotografie, No. 110, 2008; Anton Holzer: Erzählende Bilder. Fotoreportagen in der bürgerlichen und proletarischen Presse um 1930, in: Wolfgang Hesse, Holger Starke (eds.): Arbeiter, Kultur, Geschichte, Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2017, pp. 283–320.