Media-Images

Roma and Sinti in the picture press

Illustrated newspapers and magazines of the interwar period played an important role throughout Europe in shaping and disseminating images of the Roma and Sinti. Ahora, 6 June 1933, cover

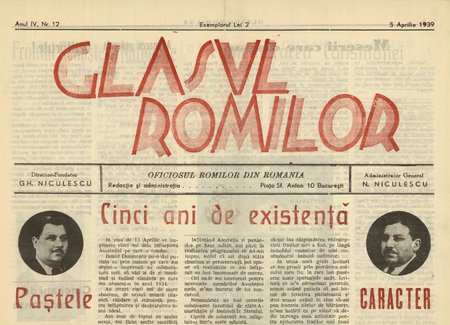

In some countries of South-Eastern Europe, alongside the mainstream media, Roma magazines emerged in the interwar period, often conveying a different, more self-assured image of the minority. Glasul Romilor, 5 April 1939, Cover (detail).

The high-circulation pictorial press of the interwar period played an important role in the development, consolidation and dissemination of photographic images of Roma and Sinti.

Nothing is as old as yesterday's newspaper, as the saying goes. The news, but above all the printed photographs contained in historical newspapers, especially illustrated newspapers and magazines, may long be a thing of the past. And yet they form an extremely fascinating cultural, social, and photographic historical archive that has been overlooked for far too long. If you want to study the history of how Roma and Sinti have been represented, historical newspapers are an outstanding source of material that has been little used in relation to photography to date.

The photographic representation and documentation of Roma and Sinti dates back to the mid-sized 19th century.[1] Many of the motifs and image patterns that recur frequently in photography have a long history in both literary and non-literary texts.[2] Photographic images were also greatly influenced by print graphics, which shaped the image of this minority group, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries. A whole series of textual and pictorial motifs and patterns were adopted, further developed and transformed by photography in the second half of the 19th century and finally in the 20th century.[3] Until the advent of mass reproduction of photographs in the illustrated press around 1900[4], these photographic images were not widely distributed.[5] Parallel to this development, the publishing boom of photographically illustrated postcards also began at the turn of the 20th century. This mass medium brought, along with the pictorial press, the mostly stereotypical motifs of Roma and Sinti to a wide audience.

When the first printed photos appeared in weekly newspapers in the 1890s, they did not initially cause much of a sensation among the public. Even in the years that followed, particularly dramatic events continued to be captured in the form of drawings. The rise of press photography did not happen overnight, but over a longer period of time. By the end of the First World War at the latest, photo printing had become completely established. The circulation of illustrated newspapers rose sharply in the 1920s – the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung (BIZ), the world's leading illustrated newspaper in the interwar period, set a global record in 1929 with a circulation of 1,892,270 copies per week.

In the years after 1900, but especially in the interwar period illustrated newspapers and magazines experienced enormous increases in circulation in many European countries[6] and rose – alongside film – to become the visual mass medium with the widest reach.[7] Illustrated newspapers retained this role into the 1950s, 1960s and, in some cases, into the 1970s, when television emerged as a new, wide-reaching visual competitor.[8] The photographs published in the early picture press have left their mark on the collective perception of Roma and Sinti to this day. Some contemporary visual representations still draw on image patterns and conventions of representation that were published in the early mass media.

Printed press photos are always part of a complex media ensemble. They are often embedded in text messages and surrounded by other images (photos, graphics, or advertisements). Sometimes they are arranged in series or sequences. They are used to fill the front page or embedded in a block of text, and may or may not be captioned. Finally, there are numerous connections that extend beyond the individual newspaper page. Many contextual and aesthetic connections and design nuances only become apparent when leafing through the paper, i.e., when consciously looking beyond the individual page (or double page) and considering developments in a longitudinal perspective.

The interpretation and analysis of press photos within their original context of use, i.e., embedded in a broader media ensemble, has proven to be particularly fruitful in research. This also applies to photographs of Roma and Sinti. Analyzing these photographs in their contemporary context of use and in connection with newspaper texts opens up new possibilities for interpretation. You run the risk of writing a history of the minority in pictures based on randomly preserved individual photos. However, it is also important to emphasize that newspaper reporting in the mainstream media always represents an outside view, which is associated with numerous stereotypes and projections.

Photographic representations of Romani and Sinti people in illustrated newspapers and magazines often oscillated between visual strategies of cultural, social and racist exclusion and marginalisation and stereotypical forms of idealisation, for example in the form of the topos of a supposedly ‘free’ and ‘nomadic life’, whereby it was not uncommon for both image strategies to be closely intertwined.

Parallel to the frequently used stereotypical images in the mainstream media, the civil emancipation movements of the minority in some countries of South-Eastern Europe also gave rise to Roma-owned magazines that presented different, more self-confident images of the minority, which will also be examined in the research project ‘Representing Roma and Sinti’ and linked to mainstream representations.[9] Among other things, the research project will examine whether and to what extent the stereotypical and hierarchical representations differ from the minority's self-representations. Were there opportunities to counter the hegemonic and hierarchical images with alternative forms of representation?

A.H.

[1] For the earliest photographic representations of Roma from the 1850s, see Anton Holzer: In the Shadow of the Crimean War. Ludwig Angerer's photographic expedition to Bucharest (1854 to 1856) in: Peter Pakesch, Verena Formanek (eds.): Seeing Carmen. Goya. Courbet. Manet. Nadar. Picasso, Cologne: Walther König, 2005, pp. 284–337.

[2] See, for example, Deborah Epstein Nord: Gypsies and the British Imagination 1807–1930, New York: Columbia University Press, 2006; Klaus-Michael Bogdal: Europe and the Roma: A History of Fascination and Fear, London: Allan Lane, 2023, first (german) edition: Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2011; Hans Richard Brittnacher: Leben auf der Grenze: Klischee und Faszination des Zigeunerbildes in Literatur und Kunst, Göttingen: Wallstein, 2012.

[3] For a broad overview of Roma photography in the 19th and 20th centuries, see Frank Reuter: Der Bann des Fremden: Die fotografische Konstruktion des “Zigeuners” (The Spell of the Foreign: The Photographic Construction of the ‘Gypsy’), Göttingen: Wallstein, 2014.

[4] Some photographs were converted into wood engravings and published in newspapers even before the 1890s.

[5] See, for example, Ilsen About, Mathieu Pernot, Adèle Sutre: Mondes Tsiganes: La Fabrique des images. Un histoire photographique 1860–1980 (Gypsy Worlds: The Making of Images. A Photographic History 1860–1980), Arles: Actes Sud, 2018; Paloma Gay y Blasco, Dina Jordanova (Hg.): Picturing Gypsies: Interdisciplinary approaches to Roma Representation, Third Text-Critical Perspectives on contemporary art and culture, Vol. 22, (special) issue 3, Abingdon: Francis & Taylor, 2008; Jodie Matthews: The Gypsy Woman. Representations in Literature and Visual Culture, London: I.B. Tauris/Bloomsbury, 2018.

[6] See Mats Jönsson, Louise Wolthers, Niclas Östlind (eds.): Thresholds. Interwar Lens Media Cultures 1919–1939, Cologne: Walther König 2021.

[7] See Tim Satterthwaite, Andrew Thacker (eds.): Magazines and Modern Identities. Global Cultures of the Illustrated Press, 1880–1945, London: Bloomsbury, 2023; Sarah Newman, Matt Houlbrooke: The Press and Popular Culture in Interwar Europe, London: Routledge, 2014.

[8] Jason E. Hill, Vanessa R. Schwartz (eds.): Getting the Picture. The Visual Culture of the News, London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2015.

[9] See the research and publications by Elena Mariushiakova, Vesselin Popov, Petre Matei, Sofiya Zahova and others. See, for example, Elena Marushiakova, Vesselin Popov (eds.): Roma Voices in History. A Sourcebook, Paderborn: Brill/Schöningh, 2021; Elena Marushiakova, Vesselin Popov (eds.): Roma Portraits in History. Roma Civic Emancipation Elite in Central, South-Eastern Europe from the 19th Century until World War II, Paderborn: Brill/Schöningh, 2022; Elena Marushiakova, Vesselin Popov: The first Gygsy/Roma Organisations, Churches and Newspapers, in: Maja Kominko (ed.): From Dust to Digital. Ten Years of Endangered Archives Programme, Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2015, pp. 189–224; Petre Matei: Between Nationalism and Pragmatism: The Roma Movement in Interwar Romania, in: Social Inclusion (issue “Gypsy Policy and Roma Activism: From the Interwar Period to Current Policies and Challenges”, edited by Elena Marushiakova and Vesselin Popov), 2020, Volume 8, No 2, pp. 305–315; Petre Matei: Women’s participation in the interwar Roma movement in Romania, in Romani Studies, 33 (1), 2023, pp. 31–54.