Roma school in Uzhorod

A paternalistic-colonialist project in Eastern Slovakia

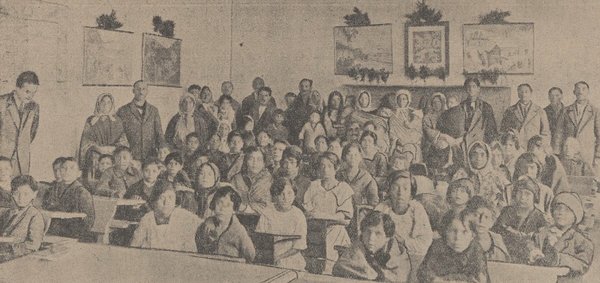

Anonymous: The ‘Roma school’ in Užhorod, eastern Slovakia (now western Ukraine), interwar period.

Anonymous: Pupils and teachers of the ‘Roma School’ in Uzhhorod, Ceske Slovo, 16 July 1927.

Founded in 1926, the Roma school in Užhorod in eastern Slovakia was considered a media sensation during the interwar period. It became a kind of magnifying glass for a wide variety of projections of a culture imagined as different.

The ‘Roma school’, which opened on 22 December 1926 near the Roma settlement on the outskirts of the city of Užhorod in eastern Slovakia, caused a great political and media stir in the interwar period. The school project was associated with high expectations in Czechoslovakia and far beyond. In the eyes of the authorities, it was primarily an educational project that was intended to help ‘civilise’ the culturally ‘backward’ eastern border region at the foot of the Carpathian Mountains. Before the First World War, the region around Užhorod belonged to the Hungarian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; after 1918, it was the eastern Slovakian border region of the newly founded Czechoslovakia. Today, Užhorod is located in the far west of Ukraine.

It was no coincidence that this project of ‘civilising’ the multi-ethnic and multi-denominational border region initially targeted the Roma minority. From the perspective of the central state elites, the Roma occupied the lowest (and most alien) rung on the imagined cultural ladder. The motto was: ‘Civilisation through education’. The first initiatives to establish a facility for the education and care of Roma children in the eastern Slovakian city, separated spatially (and socially) from other urban schools, date back to the early 1920s. The local school authorities had found that almost 90 per cent of Roma children had no school education. However, it was not possible to raise the funds for the construction of a school at that time. A few years later, in 1926, the mayor of the city, together with officials from the Ministry of Education, made a new attempt.[1]

This time they were successful. Through a skilfully coordinated media campaign, they managed not only to convince the local and national school authorities of the project, but also to win over prominent Czech politicians and business leaders. Even the Czech President Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1850–1937) made the project his personal cause and donated a large sum for the construction of the school, as did the large, internationally active shoe factory ‘Baťa’, which was based in Zlín, Moravia. From the outset, the project had paternalistic and colonialist overtones, which were only superficially concealed by including the ‘affected parties’, namely members of the Užhorod Roma community, in the group of applicants for the construction of the school. Their illiterate representatives left their fingerprints on the letter that the mayor had written at the beginning of 1926 and sent to the Czech Ministry of Education.[2] The Roma group was, of course, ‘involved’ in the project in other ways as well. Its members were obliged, for example, to lend a hand in the construction itself and to produce a total of 19,000 bricks for the building.[3]

A newspaper report that appeared in the Czech newspaper Ceske Slovo in mid-1927 was the first to feature pictures of the school.[4] The moderately high-quality photo, taken inside the new school, shows the pupils and teachers in a classically staged group photo. Media interest in the school and its mission grew rapidly in the following years. Soon, other journalists and reporters travelled to Uzhhorod to portray what was unanimously described as the ‘world's first’ ‘Roma school’.[5] Gradually, the school in Uzhhorod (which was followed by other similar school foundations in eastern Slovakia) became known in the national and later also in the international media. In the 1930s, the school became a kind of magnifying glass for a wide variety of projections of a culture imagined as different. Photography played an important role in this staging of the foreign. In conjunction with the texts, it was often images that made it possible to clothe deeply rooted ideas and imaginations in concrete, vivid scenes. Essentially, photography functioned as an instrument of the outside gaze, further reinforcing the long-standing hierarchical gaze regime towards the minority. This is because virtually all the photos taken in and around the school in the 1930s were taken by non-members of the minority. With the exception of the adult teachers, almost all of those portrayed were members of the minority. The images were published exclusively in media that were published, edited and also read by non-Roma.

English excerpt from:

Anton Holzer: Bilder im Kopf. Die „Roma-Schule“ in Užhorod. Fotografische Konstruktionen des Fremden, in: Fotogeschichte. Beiträge zur Geschichte und Ästhetik der Fotografie, No. 174, 2024, pp. 18–23.

[1] For information on the establishment and political and social background of the school project, see: Pavel Baloun: ‘Civilising the Gypsy Child’: “Gypsy School” as a Colonial Practice in Interwar Czechoslovakia (1918–1938), Telciu Summer Conferences, 4th ed., 2015 (https://www.academia.edu/30094826/). (last accessed: 24 October 2025)

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4]Ceske Slovo, 16 July 1927, p. 3.

[5] This claim is incorrect, as months earlier, in January 1926, a so-called ‘Gypsy School’ had been opened in Hurtwood (in the county of Surrey) in southern England, which remained in operation until 1931.