Violins on the wall

Photographic constructions of the Other

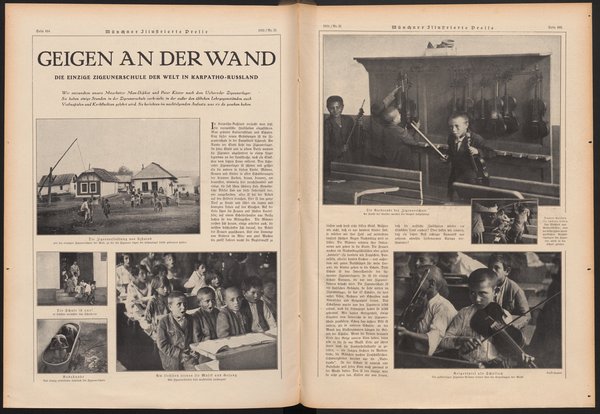

“Violins on the Wall,” photo reportage by Felix H. Man and Peter Köster (Dephot), Münchner Illustrierte Presse, 25 May 1931.

Ferdinand Bučina: Roma boys playing the violin, Uzhhorod, 1936.

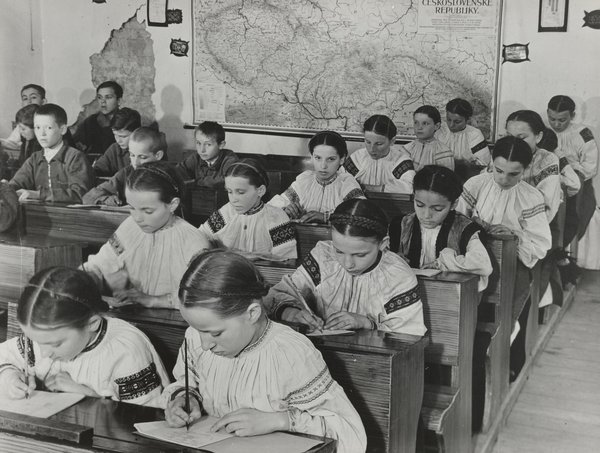

Margaret Bourke-White: School class in the Carpathian region in eastern Slovakia (now western Ukraine), 1938.

Photo reports on the Roma school in Užhorod provide an excellent example of the visual strategies of exoticisation. Photos and texts stage a seemingly unbridgeable distance between Western bourgeois civilisation and the Roma way of life.

On 25 May 1931, the Münchner Illustrierte Presse published a double-page photo reportage on the ‘only gypsy school in the world’, as the subtitle put it.[1] It was located in ‘Carpatho-Russia’. This refers to the Carpathian region in eastern Slovakia, which had belonged to the Hungarian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire before the First World War and became part of the newly founded Czechoslovakia after 1918. Today, the area lies in the far west of Ukraine. ‘We sent our employees Man-Dephot and Peter Köster to the Uzhorod gypsy camp,’ reads the introduction to the article. ‘They (...) report on what they saw there in the following essay.’ The photographs published in the report under the title ‘Violins on the Wall’ were taken in the city of Užhorod, which had a population of just under 30,000 in 1930 (today it has over 100,000).

Around 1930, the Münchner Illustrierte Presse was one of the most influential and widely circulated illustrated weekly newspapers in Germany (alongside the market leader Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung). Since 1928, the editor-in-chief had been Stefan Lorant (1901–1997), who was originally from Hungary. The reportage was photographed by Felix Sigismund Baumann, who worked as a photojournalist under the name Felix H. Man (1893–1985) and was one of Germany's best-known press photographers in the interwar period. The text of the report was written by the Hungarian journalist László Fekete (1896–1971), who had been living in Berlin since the early 1920s. Under the pseudonym Peter Köster, he initially worked as editor and publisher of the Bilder-Courier before becoming managing director (under the name Ladislaus Glück) of the small, innovative Berlin photo agency Dephot in 1931 (Deutscher Photodienst), which conceived, produced and sold groundbreaking reports to major picture newspapers between 1928 and 1933.[2] In addition to his work as managing director, Fekete was also involved in the conception of the graphic design and text for many reports. He worked closely with Felix H. Man, who had been photographing for ‘Dephot’ since mid-1929 and had soon risen to become the agency's most published and highest-earning photojournalist. His pictures were published in the press under the abbreviation ‘Man-Dephot’.

The reportage begins with a photographic overview of the ‘gypsy camp’. The accompanying text begins with an ironic and smug undertone: ‘In Carpatho-Russia, attempts are now being made to introduce civilisation.’ This condescending opening already hints at the futility of the civilising project. The following description of the everyday life of the Roma minority paints a stark contrast to this ‘civilisation’. The author, Peter Köster, plays through a wide range of clichéd, racist images in a detached, ironic manner, all of which oscillate between contempt and fascination with the exotic. What can be seen are ‘men, women and children in all shades of brown, brown, browner, brownest, swarming here in confusion, and some who are almost black.’ Everyday life in the ‘gypsy camp’ is predominantly characterised by idleness. "The men loiter around, some of them work, but most of them just watch the women work. And a huge number of children aged between two weeks and twelve years provide the accompanying music to this otherwise noisy happiness. If we did not know that there were only a hundred children, we would estimate their number to be at least a thousand.‘

About halfway through the text, the tone suddenly changes. As a counterpoint to the described bustle of a foreign, “uncivilised” community, which is described as a ’wild horde‘, the new ’Roma school" is introduced: It is ‘the most interesting thing about the Uzhorod gypsy camp,’ as it is ‘the only school in Europe attended exclusively by gypsy children.’ This shift in argument is also reflected in the images, with the camera moving in several stages from the outside to the inside. The poorly dressed children sit close together at their school desks. But the impression of a ‘normal’ school, briefly hinted at in the text, is deceptive. For the images in the reportage do not show the ordinary, but the unusual; not the everyday routine of school lessons, but the signs of difference. It begins with the fact that entry into the school is linked to a ritual of purification. We see a tin bathtub in which two children are sitting and washing themselves. ‘Bath time. The only unpopular subject at the gypsy school,’ reads the caption below the picture. ‘Every child must bathe twice a week.’

‘Even the external appearance is different from other schools. The pupils' violins hang on the classroom wall.’ According to the text, the 42 pupils at the school learn not only to read, write and do arithmetic, but also to read music and play the violin. Like the text, the photographs in the reportage also seek out the differences from a ‘normal’ school. We see the ‘violins on the wall’ already mentioned in the title, as well as children engrossed in playing the violin. ‘When the little brown boys have their violins under their chins,’ the text says, ‘there is only music for them.’ Handicrafts is the second atypical school subject that is particularly highlighted in the pictures and text as typical of the Roma community. ‘They seemed to really enjoy the handicrafts lesson – the boys weave wicker baskets, the girls make little clay bowls.’

At the end of the report, the story comes full circle. The idea of ‘civilisation’ comes into play again. The sceptical tone with which the picture story began is now taken up again. The conclusion oscillates between fascination and exoticism on the one hand and the (futile) hope for the integration of the foreign into ‘Western civilisation’ on the other. The final sentence of the report reads: "Should we rejoice that Western civilisation has conquered another piece of land? Or should we mourn the disappearance of the last remnants of true romanticism from our already colourless Europe?‘

The photo reportage presented here is a prime example of how popular the theme of the fascinating and at the same time frightening ’foreign" was in the high-circulation, popular visual media of the interwar period. In particular, the photographic representation of Roma and Sinti (who were consistently referred to as ‘Zigeuner” (gypsies)[3] in contemporary german diction) experienced a rapid upswing during these years; indeed, one can speak of a photographic hype. It is no coincidence that this wave of fascination with the exotic occurred at a time of profound social upheaval and crisis. These included the aftermath of the First World War, the economic crisis that began in many countries in the late 1920s, rising unemployment, and the rise of populist, revanchist and racist parties and movements in numerous European countries. Against this backdrop, the images and stories about Roma and Sinti circulating in popular journalism took on very specific functions. The photographic reports about the foreign can also be interpreted as spaces for playing out and echoing bourgeois desires, longings and fears.[4] In a historical phase in which bourgeois self-image and self-confidence had become fragile, illustrated magazines repeatedly offered their reading and viewing ‘armchair travellers’ photographic stories that took them on excursions into foreign, fascinating worlds, whose temptations and threats were presented in a dialogue between image and text.

Related to this, the reports reflect the growing need, in a time of crisis and uncertainty, to explore the imagined threats to the geographical, cultural and social boundaries of Western ‘civilisation’ and to redraw the borders with the ‘uncivilised’ East and South-East of Europe. It is no coincidence that many of the picture stories about Roma and Sinti published during these years imagine the boundaries of their own Western, bourgeois ‘civilisation’. The images thus also served as imaginative and projective hinges that promised to separate the (perceived as threatened) self from the (imagined) other. They formed a kind of exoticising projection screen to outline a supposed peripheral area of European ‘civilisation’ and to re-establish the ‘borders of civilisation’. These borders are to be understood geographically, but even more so socially and culturally. All these aspects are explicitly or implicitly echoed in the reportage in the Münchner Illustrierte Presse.

Felix H. Man and Peter Köster only spent ‘a few hours’ at the ‘Gypsy school’, as stated in the introduction to the report. Apparently, that was all they needed, because they already had the images they were looking for in their minds. They were neither the first nor the last ‘Western’ visitors to travel to Uzhhorod to photographically stage the ‘Roma school’ as a projection screen for exoticism and a stage for exclusion and marginalisation. When the Czech amateur photographer and photojournalist Ferdinand Bučina (1909–1994) visited the city in eastern Slovakia in the summer of 1936 (during his honeymoon), he documented the now famous ‘Roma school’ with his camera. He, too, shows the Roma youths engaged in a ‘typical’ activity, playing the violin on the street. His pictures were later published in the Prague-based weekly magazine Ahoj na neděli (Hello to Sunday).

It is striking that these and other photographic reports from those years, which used the media coverage of the “Roma school” in Užhorod as a starting point and hook for their reporting, seamlessly continue the clichéd images of an exotic counterworld in their iconography and motifs, as these had been created in photography since the 19th century.[1] The Roma school, which had started with lofty promises of emancipation, became, in the various reports compiled in the 1930s, a prime example of a seemingly unbridgeable civilisational distance between one's own world and that of others. Ultimately, however, the photo reports also conclude that the project of ‘civilisation through education’ is doomed to failure.

In 1938, two years after Ferdinand Bučina visited the city of Užhorod, the well-known American photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971), who worked for Life magazine among others, travelled to eastern Slovakia with her husband, the writer Erskine Caldwell (1903–1987).[2] She also visited Uzhhorod. One of her pictures, taken on her trip through eastern Slovakia, shows a view into a classroom. The pupils sit at their desks, separated by gender. The girls are dressed in robes with traditional embroidery in the style of Carpathian Ukrainian folk culture. It is immediately clear that this cannot be the ‘Roma school’. The national borders of the state are demonstratively brought into the picture in the form of a map of Czechoslovakia hanging on the wall. The photographer also photographed pupils at a Jewish Talmud school in Užhorod. Significantly, the Roma school, which just a few years earlier had been praised as a spark of hope for a ‘civilising’ development project and repeatedly documented in photographs, does not appear in Bourke-White's photo series. However, she does show members of the Roma community in her pictures, namely in their miserable dwellings.[3] [7] From the American photographer's perspective, the ‘civilisational’ gap between the Roma and non-Roma groups now seems completely unbridgeable. Bourke-White's photographs from 1938 are among the last photographic records of the Transcarpathian Roma community before the Second World War. The war that was about to begin brought with it a wave of violence that had a particularly destructive effect on the multi-ethnic and multi-religious border region. The Roma communities of Užhorod, along with the Jewish and parts of the Ukrainian populations, were caught up in a maelstrom of persecution, deportation and murder, the consequences of which are still felt today.[4]

English Excerpt from:

Anton Holzer: Bilder im Kopf. Die „Roma-Schule“ in Užhorod. Fotografische Konstruktionen des Fremden, in: Fotogeschichte. Beiträge zur Geschichte und Ästhetik der Fotografie, No. 174, 2024, pp. 18–23.

[1] For more details, see Frank Reuter, Der Bann des Fremden: Die fotografische Konstruktion des “Zigeuners” (The Spell of the Foreign: The Photographic Construction of the ‘Gypsy’), Göttingen, 2014.

[2] The reason for the trip that took Bourke-White and Caldwell across Czechoslovakia was the threat to the sovereignty of the Czech Republic posed by Nazi Germany. This political crisis came to a head in the summer of 1938 and ultimately led to the dismantling of Czechoslovakia in September/October 1938. Bourke-White reported on this in Life magazine in 1938. Bourke-White and Caldwell's travel reports from Czechoslovakia were also published the following year in the photo book North of the Danube, New York 1939.

[3] See Margaret Bourke-White, Erskine Caldwell: North of the Danube, New York: Viking Press, 1939.

[4] Historian Raz Segal traces in detail the complex and often intertwined developments of violence (as well as the role of Nazi German, Hungarian, and Ukrainian nationalist politics) in the border region of the Carpathians: Genocide in the Carpathians. War, Social Breakdown, and Mass Violence 1914–1945, Stanford 2016.